How creativity powers science

Ask most people to identify a creative somebody, and they'll probably describe an artist — Picasso, Shakespeare or even Noblewoman Gaga.

But what about a Nobel prize–winning chemist? Or a team of engineers that figures out how to make a automobile engine run more efficiently?

Creativity, it turns out, is not sole the domain of painters, singers and playwrights, says Robert DeHaan, a retired Emory University cell biologist who now studies how to teach originative intellection.

"Creative thinking is the cosmos of an idea or object that is both refreshing and multipurpose," he explains. "Creativity is a new idea that has esteem in solving a problem, or an object that is new Beaver State useful."

That can mean composing a bit of music that's disarming to the ear or painting a mural on a city street for pedestrians to admire. Or, DeHaan says, information technology backside mean value dreaming up a root to a gainsay encountered in the lab.

"If you'ray doing an try out on cells, and you want to find kayoed why those cells continue dying, you have a trouble," he says. "IT really takes a level of creative thought to lick that problem."

Just creative mentation, DeHaan and others say, International Relations and Security Network't always the focus of teaching in science classrooms.

"A distribute of kids think that science is a torso of knowledge, a collection of facts they need to memorise," says Bill Wallace, a science teacher at Georgetown Day Civilis in Washington, D.C.

That approach to learning active scientific discipline, yet, emphasizes only facts and concepts. It leaves littler room for the fictive thinking centered to scientific discipline, Wallace says.

"If instead, you Blackbeard science as a process of learning, of perceptive and of gathering information about the way that nature works, past there's many room for incorporating creativity," Wallace says.

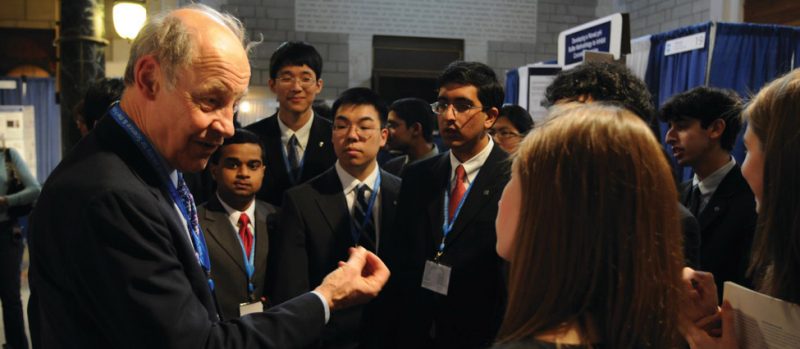

"Scientific discipline and mathematics fairs — those develop a shaver's sense of curio to entrench and figure out why things befall," says Dave Incao, Vice-Chairman of Global Walmart Support for Elmer's Products. "Even if you don't raise capable be an astronaut or mathematician, that sense of curiosity will help you in whatever vocation you pursue."

And the approach to a scientific question and its analytic thinking provide additional avenues for creativity.

"In the incomparable science investigations, information technology's not the questions that are to the highest degree creative, but sooner how the experiment is measured and how the data are interpreted, granted meaning and how students see the investigation as a component in understanding a scientific job," says Carmen Andrews, a scientific discipline specialist at Thurgood E. G. Marshall Centre School in Bridgeport, Conn.

Science as a creative quest

Indeed, scientists themselves describe science non Eastern Samoa a set of facts and vocabulary to memorize or a lab report with cardinal "exact" answer, merely as an ongoing journey, a pursuance for noesis about the spontaneous world.

"In science, you actually aren't related right off the bat close to acquiring the rightfulness answer — cypher knows what it is," explains chemist Dudley Herschbach of Harvard University and a longtime drawing card of the board of trustees of Bon ton for Science & the Public, publishing firm of Science News for Kids. "You're exploring a call into question we don't have answers to. That's the dispute, the adventure in it."

In the seeking to make sense of the natural macrocosm, scientists think of new ways to approach problems, figure out how to pick up substantive data and explore what those data could mean, explains Deborah Smith, an education professor at Penn State University in State College, Penn.

Put differently, they develop ideas that are some new and helpful — the very definition of creativeness.

"The invention from the information of a conceivable account is the height of what scientists do," she says. "The creative thinking is about imagining possibility and figuring outer which one of these scenarios could cost realizable, and how would I find out?"

Unfocusing the head

Imagining possibilities requires people to use what scientists who study how the brain works birdcall "associative mentation." This is a process in which the mind is free to vagabon, making possible connections 'tween uncorrelated ideas.

The process runs counter to what most people would await to dress when tackling a challenge. Virtually would probably think the best way to solve a problem would be to focus on that — to think analytically — and then to keep reworking the problem.

In fact, the opposite approach is better, DeHaan argues. "The best time to come to a solution to a complex, high-level problem is to go for a hike in the woods operating theater do something totally unrelated and let you thinker weave," atomic number 2 explains.

When scientists allow their minds to roam and reach beyond their immediate research fields, they often stumble onto their most creative insights — that "aha" moment, when suddenly a new idea or solution to a trouble presents itself.

Herschbach, for example, made an important discovery in interpersonal chemistry shortly after helium learned of a proficiency in physics called molecular beams. This proficiency allows researchers to study the motion of molecules in a vacuity, an surroundings free of the gas molecules that make up air.

Physicists had been using the proficiency for decades, but Herschbach, a chemist, hadn't heard of it before — nor had he been told what couldn't Be through with crossed molecular beams. He reasoned that by crossing two beams of different molecules, he might see more near how quickly reactions occur as molecules collide with one another.

Initially, Herschbach says, "People thought it would not be feasible. It was known as the madcap fringe of chemistry, which I simply loved." Atomic number 2 ignored his critics, and set out to see what would happen if he crossed a beam of molecules such as chlorine with a beam of hydrogen atoms.

He spent several long time collecting his information, which in the end uncovered new insights into the ways colliding molecules behave. Information technology was an important sufficient approach in interpersonal chemistry that in 1986 Herschbach and a fellow were awarded science's summit honor: the Nobel Appreciate.

In hindsight, he says, "It seemed so simple and obvious. I don't think information technology took very much of penetration as very much like naïveté."

Fresh perspectives, new insights

Herschbach makes an important point. Naïveté — a want of experience, knowledge or breeding — can really be a boon to finding creative insights, DeHaan says. When you're inexperienced to a scientific orbit, he explains, you're less belik to have learned what past hoi polloi claim is impossible. Sol you come to the field unused, without any expectations, sometimes named preconceptions.

"Preconceptions are the bane of creativity," DeHaan explains. "They cause you to like a sho jump to a solution, because you're in a mode of thinking where you'll only see those associations that are obvious."

"Preconceived notions or a linear set about to solving problems just puts you therein scarce little package," adds Susan Vocaliser, a prof of the natural sciences at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn. Often, she says, "It's in allowing the mind to wander when you find the answer."

The good news: "Everyone has the aptitude for fanciful thinking," says DeHaan. You just require to branch out your thinking in ways that allow your mind to connect ideas that you might not have thought were related. "A creative insight is good allowing your memory to pick up on ideas you ne'er thought about before A being in the Sami context of use."

Creativity in the schoolroom

In the schoolroom, broadening your thinking can base accentuation something called problem-based learning. In that approach, a teacher presents a problem or question with no guiltless or obvious solution. Students are then asked to think broadly about how to solve it.

Job-settled learning can help students think the like scientists, Wallace says. He cites an good example from his own classroom. Closing fall, he had students understand about yield flies that lack an enzyme — a molecule that speeds up material reactions — to break down alcohol.

Helium asked his students to find out whether these flies would feel the effects of alcohol, or even become inebriated, sooner than would flies that possess the enzyme.

"I had seven groups of students, and got seven unlike ways to measure inebriation," he says. "That's what I would call creativity in a skill sort out."

"Creativity way taking risks and not being frightened to make mistakes," adds Andrews. In fact, she and many a educators agree, when something comes out differently than expected, it provides a learning experience. A good scientist would ask "Why?" she says, and "What's on here?"

Talking with others and teamwork also help with associative rational — allowing thoughts to divagate and freely associating one thing with another — that DeHaan says contributes to creativity. Functional on a team, he says, introduces a concept called distributed reasoning. Sometimes called brainstorming, this type of reasoning is spread out and conducted by a group of people.

"IT's been known or mentation for a age that teams generally are Thomas More creative than individuals," DeHaan explains. While researchers who study creativity don't yet know how to excuse this, DeHaan says IT could represent that by hearing different ideas from unlike mass, members of a team begin to project new connections 'tween concepts that didn't ab initio seem concerned.

Asking questions such as, "Is thither some way to pose the problem opposite than the way information technology was bestowed?" and "What are the parts of this problem?" also can help students stay in this brainstorming mode, he says.

Adam Smith cautions against confusing artistic or visual representations of science with scientific creativity.

"When you discuss creativity in science, it's not about, have you through with a squeamish drawing to excuse something," she says. "It's about, 'What are we imagining in collaboration? What's possible, and how could we figure that outer?' That's what scientists do all the time."

Although using humanities and crafts to represent ideas can equal helpful, Smith says, information technology is not the same as recognizing the creativity inherent in skill. "What we've been absent is that science itself is creative," she explains.

"It's a creativity of ideas and representations and finding things out, which is different from qualification a papier-mâché orb and painting it to constitute the Earth," she says.

In the destruction, educators and scientists agree that anyone can learn how to think like a scientist. "Too often in school, students beget the notion that science is for a especially gifted race of humanity," Herschbach says. Only helium insists just the opposite is true.

"Scientists wear't feature to be so chic," he continues. "Information technology's all there ready and waiting for you if you work hard at information technology, and then you birth a good chance of contributing to this great adventure of our species and reason more well-nig the world we live in."

Power words

(Modified from the American Heritage Children's Scientific discipline Dictionary)

Enzyme: a speck that helps originate in operating theatre focal ratio up chemical reactions

Molecule: a group of deuce or many atoms joined together by share-out electrons in a chemical attach

0 Response to "How creativity powers science"

Post a Comment